|

Fi

By Chris Giles, Economics Editor September 28, 2014 A “poisonous combination” of record debt and slowing growth suggest the global economy could be heading for another crisis, a hard-hitting report will warn on Monday. The 16th annual Geneva Report, commissioned by the International Centre for Monetary and Banking Studies and written by a panel of senior economists including three former senior central bankers, predicts interest rates across the world will have to stay low for a “very, very long” time to enable households, companies and governments to service their debts and avoid another crash. The warning, before the International Monetary Fund’s annual meeting in Washington next week, comes amid growing concern that a weakening global recovery is coinciding with the possibility that the US Federal Reserve will begin to raise interest rates within a year. One of the Geneva Report’s main contributions is to document the continued rise of debt at a time when most talk is about how the global economy is deleveraging, reducing the burden of debts. Although the burden of financial sector debt has fallen, particularly in the US, and household debts have stopped rising as a share of income in advanced economies, the report documents the continued rapid rise of public sector debt in rich countries and private debt in emerging markets, especially China. It warns of a “poisonous combination of high and rising global debt and slowing nominal GDP [gross domestic product], driven by both slowing real growth and falling inflation”. The total burden of world debt, private and public, has risen from 160 per cent of national income in 2001 to almost 200 per cent after the crisis struck in 2009 and 215 per cent in 2013. “Contrary to widely held beliefs, the world has not yet begun to delever and the global debt to GDP ratio is still growing, breaking new highs,” the report said. Luigi Buttiglione, one of the report’s authors and head of global strategy at hedge fund Brevan Howard, said: “Over my career I have seen many so-called miracle economies – Italy in the 1960s, Japan, the Asian tigers, Ireland, Spain and now perhaps China – and they all ended after a build-up of debt.” Mr Buttiglione explained how, initially, solid reasoning for faster growth encourages borrowing, which helps maintain growth even after the underlying story sours. The report’s authors expect interest rates to stay lower than market expectations because the rise in debt means that borrowers would be unable to withstand faster rate rises. To prevent an even more rapid build-up in debt if borrowing costs are low, the authors further expect authorities around the world to use more direct measures to curb borrowing. The report expresses most concern about economies where debts are high and growth has slowed persistently – such as the eurozone periphery in southern Europe and China, where growth rates have fallen from double digits to 7.5 per cent. Although the authors note that the value of assets has tended to rise alongside the growth of debt, so balance sheets do not look particularly stretched, they worry that asset prices might be subject to a vicious circle in “the next leg of the global leverage crisis” where a reversal of asset prices forces a credit squeeze, putting downward pressure on asset prices. A History Note On Mises’s View Of The Business Cycle And The Wicksellian “Natural” Rate Of Interest by Murray N. Rothbard September 29, 2014 From The Essential von Mises: Included in The Theory of Money and Credit were at least the rudiments of another magnificent accomplishment of Ludwig von Mises: the long-sought explanation for that mysterious and troubling economic phenomenon — the business cycle. Ever since the development of industry and the advanced market economy in the late eighteenth century, observers had noted that the market economy is subject to a seemingly endless series of alternating booms and busts, expansions, sometimes escalating into runaway inflation or severe panics and depressions. Economists had attempted many explanations, but even the best of them suffered from one fundamental flaw: none of them attempted to integrate the explanation of the business cycle with the general analysis of the economic system, with the “micro” theory of prices and production. In fact, it was difficult to do so, because general economic analysis shows the market economy to be tending toward “equilibrium,” with full employment, minimal errors of forecasting, etc. Whence, then, the continuing series of booms or busts? Ludwig von Mises saw that, since the market economy could not itself lead to a continuing round of booms and busts, the explanation must then lie outside the market: in some external intervention. He built his great business cycle theory on three previously unconnected elements. 1. One was the Ricardian demonstration of the way in which government and the banking system habitually expand money and credit, driving prices up (the boom) and causing an outflow of gold and a subsequent contraction of money and prices (the bust). Mises realized that this was an excellent preliminary model, but that it did not explain how the production system was deeply affected by the boom or why a depression should then be made inevitable. From these three important but scattered theories, Mises constructed his great theory of the business cycle. Into the smoothly functioning and harmonious market economy comes the expansion of bank credit and bank money, encouraged and promoted by the government and its central bank. As the banks expand the supply of money (notes or deposits) and lend the new money to business, they push the rate of interest below the “natural” or time preference rate, i.e., the free-market rate which reflects the voluntary proportions of consumption and investment by the public.

As the interest rate is artificially lowered, the businesses take the new money and expand the structure of production, adding to capital investment, especially in the “remote” processes of production: in lengthy projects, machinery, industrial raw materials, and so on. The new money is used to bid up wages and other costs and to transfer resources into these earlier or “higher” orders of investment. Then, when the workers and other producers receive the new money, their time preferences having remained unchanged, they spend it in the old proportions. But this means that the public will not be saving enough to purchase the new high-order investments, and a collapse of those businesses and investments becomes inevitable. The recession or depression is then seen as an inevitable re-adjustment of the production system, by which the market liquidates the unsound “over-investments” of the inflationary boom and returns to the consumption/investment proportion preferred by the consumers. Mises thus for the first time integrated the explanation of the business cycle with general “micro-economic” analysis. The inflationary expansion of money by the governmentally run banking system creates over-investment in the capital goods industries and under-investment in consumer goods, and the “recession” or “depression” is the necessary process by which the market liquidates the distortions of the boom and returns to the free-market system of production organized to serve the consumers. Recovery arrives when this adjustment process is completed. The policy conclusions implied by the Misesian theory are the diametric opposite of the current fashion, whether “Keynesian” or “post-Keynesian.” If the government and its banking system are inflating credit, the Misesian prescription is (a) to stop inflating posthaste, and (b) not to interfere with the recession-adjustment, not prop up wage rates, prices, consumption or unsound investments, so as to allow the necessary liquidating process to do its work as quickly and smoothly as possible. The prescription is precisely the same if the economy is already in a recession. Julia La Roche

Business Insider Sepember 22, 2014 Legendary hedge fund manager Julian Robertson gave a warning about two bubbles that could "bite us" at Bloomberg Market's Most Influential Summit. "I agree with the fact that the economy is definitely getting better. I think the cause of that is two bubbles that will bite us. The first bubble is that bonds are at ridiculous levels...The small saver has no place to put his money except stocks. I think that the situation is serious on that score. No one seems to be concerned about that. It's a world-wide phenomenon that countries are buying bonds to keep them moving along economically." He said he doesn't know when it will end, but it will be in a "very bad way." Bill Conway from the Carlyle Group was also on the panel. Conway later said that he agrees with the bubble idea intellectually, but he didn't see a catalyst that will cause it to burst. Robertson also said that there are some "great companies around" to invest in. He said that Alibaba, which became public last week, is a "fabulous company." "If Alibaba and some of the other things do as well as they are projected to do, then they are probably reasonable valued. Look, we are always looking for bargains...that's sort of the way it goes in our business," he said later on the panel. Last week, CalPERS said they would redeem from all their hedge fund investments citing fees and complexity. CalPERS only had $4 billion allocated to funds. Robertson said that he didn't think their move was all that important for the industry. "Well it's less than 1% of their holdings. They weren't very seriously involved. I think it's definitely much harder to run a hedge fund today than it used to be. In my opinion, it's because there are more hedge funds to compete with. We had a field day before anyone knew anything about shorting. It was almost a license to steal. Nowadays it's a license to get hosed." The moderator asked Robertson about returns in the hedge fund space. "I think that depends on the way you run your hedge fund. A lot of people are running hedge funds, a lot of very good people are running hedge funds, and you really couldn't say that these things are 'hedge funds' because they might be 30 percent hedged, but that's about it. They're almost no truly 'hedge funds'--one hundred percent hedged. I think it's still, particularly a good thing in view of the bubble, to have an anchor windward." He said that the worst situation he's seen in the markets was October 1987 and it just "came out of the blue." "There really was no reason for that. The economy was strong. There was a bubble and it was pricked and boom!" Read more: http://www.businessinsider.com/julian-robertson-bloomberg-panel-2014-9#ixzz3EAVBPcGL By John Mauldin September 21, 2014 It’s About Your Presuppositions In 1633 Galileo Galilei, then an old man, was tried and convicted by the Catholic Church of the heresy of believing that the earth revolved around the sun. He recanted and was forced into house arrest for the rest of his life, until 1642. Yet “The moment he [Galileo] was set at liberty, he looked up to the sky and down to the ground, and, stamping with his foot, in a contemplative mood, said, Eppur si muove, that is, still it moves, meaning the earth” (Giuseppe Baretti in his book the The Italian Library, written in 1757). Flawed from its foundation, economics as a whole has failed to improve much with time. As it both ossified into an academic establishment and mutated into mathematics, the Newtonian scheme became an illusion of determinism in a tempestuous world of human actions. Economists became preoccupied with mechanical models of markets and uninterested in the willful people who inhabit them…. And to that stirring introduction let me just add a warning up front: today’s letter is not exactly a waltz in the park. Longtime readers will know that every once in a while I get a large and exceptionally aggressive bee in my bonnet, and when I do it’s time to put your thinking cap on. And while you’re at it, tighten the strap under your chin so it doesn’t blow off. There, now, let’s plunge on. Launched by Larry Summers last November, a meme is burning its way through established academic economic circles: that we have entered into a period of – gasp! – secular stagnation. But while we can see evidence of stagnation all around the developed world, the causes are not so simple that we can blame them entirely on the free market, which is what Larry Summers and Paul Krugman would like to do: “It’s not economic monetary policy that is to blame, it’s everything else. Our theories worked perfectly.” This finger-pointing by Keynesian monetary theorists is their tried and true strategy for deflecting criticism from their own economic policies. Academic economists have added a great deal to our understanding of how the world works over the last 100 years. There have been and continue to be remarkably brilliant papers and insights from establishment economists, and they often do prove extremely useful. But as George Gilder notes above, “[As economics] ossified into an academic establishment and mutated into mathematics, the Newtonian scheme became an illusion of determinism in a tempestuous world of human actions.” Ossification is an inherent tendency of the academic process. In much of academic economics today, dynamic equilibrium models and Keynesian theory are assumed a priori to be correct, and any deviation from that accepted economic dogma – the 21st century equivalent of the belief by the 17th century Catholic hierarchy of the correctness of their worldview – is a serious impediment to advancement within that world. Unless of course you are from Chicago. Then you get a sort of Protestant orthodoxy. It’s About Your Presuppositions A presupposition is an implicit assumption about the world or a background belief relating to an utterance whose truth is taken for granted in discourse. For instance, if I asked you the question, “Have you stopped eating carbohydrates?” The implicit assumption, the presupposition if you will, is that you were at one time eating carbohydrates. Our lives and our conversations are full of presuppositions. Our daily lives are based upon quite fixed views of how the world really works. Often, the answers we come to are logically predictable because of the assumptions we make prior to asking the questions. If you allow me to dictate the presuppositions for a debate, then there is a good chance I will win the debate. The presupposition in much of academic economics is that the Keynesian, and in particular the neo-Keynesian, view of economics is how the world actually works. There has been an almost total academic capture of the bureaucracy and mechanism of the Federal Reserve and central banks around the world by this neo-Keynesian theory. What happens when one starts with the twin presuppositions that the economy can be described correctly using a multivariable dynamic equilibrium model built up on neo-Keynesian principles and research founded on those principles? You end up with the monetary policy we have today. And what Larry Summers calls secular stagnation. First, let’s acknowledge what we do know. The US economy is not growing as fast as anyone thinks it should be. Sluggish is a word that is used. And even our woeful economic performance is far superior to what is happening in Europe and Japan. David Beckworth (an economist and a professor, so there are some good guys here and there in that world) tackled the “sluggish” question in his Washington Post “Wonkblog”: The question, of course, is why growth has been so sluggish. Larry Summers, for one, thinks that it’s part of a longer-term trend towards what he calls “secular stagnation.” The idea is that, absent a bubble, the economy can’t generate enough spending anymore to get to full employment. That’s supposedly because the slowdowns in productivity and labor force growth have permanently lowered the “natural interest rate” into negative territory. But since interest rates can’t go below zero and the Fed is only targeting 2 percent inflation, real rates can’t go low enough to keep the economy out of a protracted slump. Rather than acknowledge the possibility that the current monetary and government policy mix might be responsible for the protracted slump, Summers and his entire tribe cast about the world for other causes. “The problem is not our theory; the problem is that the real world is not responding correctly to our theory. Therefore the real world is the problem.” That is of course not exactly how Larry might put it, but it’s what I’m hearing.

Weekly Market Comment

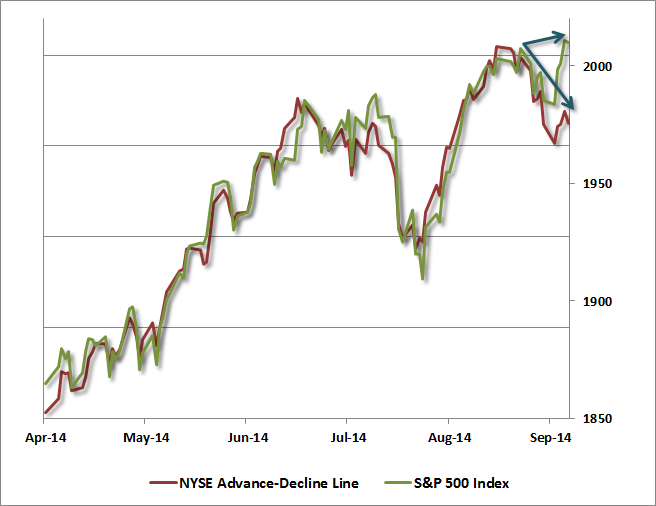

John P. Hussman, Ph.D. September 22, 2014 Market internals continue to deteriorate An important note on the equity markets: we’re observing a continued deterioration in market internals at extremely elevated valuations, much as we observed in July 2007 (see Market Internals Go Negative). Credit spreads have widened in recent weeks, breadth has deteriorated (resulting in weakness among the average stock despite marginal new highs in several major indices), and downside leadership is also increasing. As a small example that illustrates the larger point, despite the marginal new high in the S&P 500 last week, the NYSE showed more declines than advances, and nearly as many new 52-week lows as new 52-week highs. About half of all equities traded on the Nasdaq are already down 20% from their 52-week highs and below their 200-day averages. Small cap stocks have also weakened considerably relative to the S&P 500. Indeed, though it’s not a signal that factors into our own measures of market internals (and we also wouldn’t put much weight on it in the absence of deterioration in our own measures), it’s interesting that Friday also produced a “Hindenburg” signal as a result of that lack of internal uniformity: both new highs and new lows exceeded 2.5% of issues traded, the S&P 500 was above its 10-week average, and breadth as measured by advance-decline line is deteriorating. One can certainly wait for greater internal divergence before raising concerns, but my impression is that this confirmation is likely to emerge in the form of a steep, abrupt initial decline (which we call an “air pocket”). That isn’t a forecast, but an observation based on prior instances of deteriorating uniformity following extended overvalued, overbought, overbullish periods. This time may be different. Needless to say, we aren’t counting on that. The chart below shows the cumulative NYSE advance-decline line (red) versus the S&P 500. While the divergence is not profound, similar and broader divergences are appearing across a wide range of asset classes and security types, and it’s the uniformity of those divergences – not simply the extent – that contains information that suggests that investor risk preferences are subtly shifting toward risk aversion. Friday, September 19, 2014

(Reuters) - The Federal Reserve should start raising U.S. interest rates in the spring, earlier than many investors currently expect, and should do so both slowly and gradually, a top Fed official said on Friday. "I personally would want to see, the date of our first move, I personally expect it to occur in the spring and not in the summer as it seems the markets are discounting," Dallas Federal Reserve Bank President Richard Fisher said in an interview on Fox Business Network. Already there are signs of financial excess in markets, he said, and although inflation currently is not a problem, continued low rates could spark unwanted price pressures. Waiting too long to raise rates could ultimately force the Fed to raise them sharply, he warned, potentially driving the economy into another recession. Fisher indicated he believed rates should move up in quarter-point increments. Fisher, who was one of two dissenters at the Fed's policy meeting this week, said he was already seeing wage-price pressures in his home state of Texas, and warned the same thing could happen nationally as the unemployment rate, now at 6.1 percent, continues to fall. That's not a view that's widely held at the Fed, which on Wednesday reiterated its plan to keep rates near zero for a "considerable time" after it ends its bond-buying stimulus next month. Fed Chair Janet Yellen said the Fed's policy-setting committee was comfortable with that statement. Markets continue to price in a first rate rise in mid-2015. Fisher said Friday was seeing financial excess in markets, particularly in high-yield bonds. “I think we’ve levitated the markets,” he said. "I don't want to drive this any further, and I think we have to be aware of this." Mohamed_A_El-Erian

Posted on September 16, 2014 by Warsame in Economy LAGUNA BEACH – This has been an unusual year for the global economy, characterized by a series of unanticipated economic, geopolitical, and market shifts – and the final quarter is likely to be no different. How these shifts ultimately play out will have a major impact on the effectiveness of government policies – and much more. So why have financial markets been behaving as if they were in a world of their own? Apparently unfazed by disappointing growth in both advanced and emerging economies, or by surging geopolitical tensions in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, equity markets have set record after record this year. This impressive rally has ignored a host of historical relationships, including the long-established correlation between the performance of stocks and government bonds. In fact, correlations among a number of different financial-asset classes have behaved in an atypical and, at times, unstable manner. Meanwhile, on the policy front, advanced-country monetary-policy cohesion is giving way to a multi-track system, with the European Central Bank stepping harder on the stimulus accelerator, while the US Federal Reserve eases off. These factors are sending the global economy into the final quarter of the year encumbered by profound uncertainty in several areas. Looming particularly large over the next few months are escalating geopolitical conflicts that are nearing a tipping point, beyond which lies the specter of serious systemic disruptions in the global economy. This is particularly true in Ukraine, where, despite the current ceasefire, Russia and the West have yet to find a way to ease tensions definitively. Absent a breakthrough, the inevitable new round of sanctions and counter-sanctions would likely push Russia and Europe into recession, dampening global economic activity. Even without such complications, invigorating Europe’s increasingly sluggish economic recovery will be no easy feat. In order to kick-start progress, ECB President Mario Draghi has proposed a grand policy bargain to European governments: if they implement structural reforms and improve fiscal flexibility, the central bank will expand its balance sheet to boost growth and thwart deflation. If member states do not uphold their end of the bargain, the ECB will find it difficult to carry the policy burden effectively – exposing it to criticism and political pressure. Across the Atlantic, the Fed is set to complete its exit from quantitative easing (QE) – its policy of large-scale asset purchases – in the next few weeks, leaving it completely dependent on interest rates and forward policy guidance to boost the economy. The withdrawal of QE, beyond being unpopular among some policymakers and politicians, has highlighted concerns about the risk of increased financial instability and rising inequality – both of which could undermine America’s already weak economic recovery. Complicating matters further are the US congressional elections in November. Given the likelihood that the Republicans will continue to control at least one house of Congress, Democratic President Barack Obama’s policy flexibility will probably remain severely constrained – unless, of course, the White House and Congress finally find a way to work together. Meanwhile, in Japan, the private sector’s patience with Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s three-pronged strategy to reinvigorate the long-stagnant economy – so-called “Abenomics” – will be tested, particularly with regard to the long-awaited implementation of structural reforms to complement fiscal stimulus and monetary easing. If the third “arrow” of Abenomics fails to materialize, investors’ risk aversion will rise yet again, hampering efforts to stimulate growth and avoid deflation. Systemically important emerging economies are also subject to considerable uncertainty. Brazil’s presidential election in October will determine whether the country makes progress toward a new, more sustainable growth model or becomes more deeply mired in a largely exhausted economic strategy that reinforces its stagflationary tendencies. In India, the question is whether newly elected Prime Minister Narendra Modi will move decisively to fulfill voters’ high expectations for economic reform before his post-victory honeymoon is over. And China will have to mitigate financial risks if it hopes to avoid a hard landing. The final source of uncertainty is the corporate sector. So far this year, healthy companies have slowly been loosening their purse strings – a notable departure from the risk-averse behavior that has prevailed since the global financial crisis. Indeed, an increasing number of firms have started to deploy the massive stocks of cash held on their balance sheets, first to increase dividends and buy back shares, and then to pursue mergers and acquisitions at a rate last seen in 2007. The question is whether companies also will finally devote more cash to new investments in plant, equipment, and people – a key source of support for the global economy. This is a rather weighty list of questions. Yet financial-market participants have largely bypassed them, brushing aside today’s major risks and ignoring the potential volatility that they imply. Instead, financial investors have trusted in the steadfast support of central banks, confident that the monetary authorities will eventually succeed in transforming policy-induced growth into genuine growth. And, of course, they have benefited considerably from the deployment of corporate cash. In the next few months, the buoyant optimism pervading financial markets may prove to be justified. Unfortunately, it is more likely that investors’ outlook is excessively rosy. --- Mohamed A. El-Erian is Chief Economic Adviser at Allianz and a member of its International Executive Committee. He is Chairman of President Barack Obama’s Global Development Council and the author, most recently, of When Markets Collide. Excerpts:

We don’t know now (nor do we ever know) what the overall market will do. As we’ve discussed in recent letters, there are reasons for investors to be frightened but also numerous individual opportunities worth seizing. Today’s limited opportunity set means that we are still holding sizable cash balances, about 35% of the portfolio at June 30. This dry powder will become more valuable if the markets become more turbulent. Equity markets continue to hit successive record highs, volatility remains strikingly low in equity and most other markets, and inflation is ticking higher. Investors have clearly grown weary of worrying about risky scenarios that never seem to materialize or, when they do, don’t seem to matter to anyone else. U.S. GDP, for example, was recently restated to minus 2.9% for the first quarter of 2014. Normally, this magnitude drop signals recession. Equities, nevertheless, marched relentlessly higher. ... In today’s ebullient markets, we see many investors ratcheting up their own risk levels--buying substandard credits and piling up leverage are two favorite methods--in an attempt to generate near-term performance. ... The financial markets could be getting closer to an inflection point, where the economic weakness that the bond market seems to be reflecting derails the more optimistic equity market. Or perhaps things can go on forever exactly as they are: a “Goldilocks” stock market resulting from a tepid economy, dampened volatility, and relentlessly low interest rates. Amidst the market rally, complacent investors continue to ignore a growing array of global trouble spots. Contrary to claims from the Obama Administration, the world is not a tranquil place at present. As such, risks facing investors seem to be rising but are not yet priced into the markets. ... Late in a market cycle--when bargains are increasingly hard to find, valuations are lofty, and most investors have been scoring handsome gains for a number of years--we can say from experience that history tends to rhyme. Money becomes more freely available to pursue even the most marginal of opportunities. Dollars pour into venture capital, and the largest buy-side firms take strategic stakes in hot, late-stage private investments just prior to an expected big money IPO. Specialized funds are raised, regularly and easily, to invest in things like Greek private investments, Spanish real estate, or European non-performing loan pools. Willing investors abound for these. It doesn’t matter that market prices have mostly rebounded, prospective returns are thereby limited, and the capital in those funds is likely to be put to work whether or not prices warrant and even if conditions on the ground deteriorate. With investment bankers and hedge fund executives canvassing Europe today to bet on recovery, you have the increasingly common circumstance of proliferating “opportunity funds,” absent only the investment opportunity. Some clients of hedge funds today are, in a sense, disintermediating themselves, funding new entities to bid higher for the same sort of assets their other, more disciplined managers are already bidding more judiciously for. The discipline problem in this case is not that of the legacy managers; it may just be that of the clients. The pressure to reach for return virtually ensures that many investors will take greater and greater risk for less and less potential reward at market peaks. If you can’t find bonds that yield 8%, better grab those offering 6%. Or 4%. If you need 8% to meet your bogey (assumed pension fund returns, for example, or promised returns to investors), then you will be prone to own increasingly risky assets or leverage up the safer ones. These pressures, as much as any indicator, are today signaling danger. Investors today are bidding ever higher amidst frenzied competition to buy pools of non-performing loans, and then leveraging them up to get double-digit returns. Mortgage securities backed by questionable loans issued to dicey borrowers now trade close to par and yield a downright stingy 3-5% where they once yielded a generous 15-20%. A recent brokerage report excitedly touted the new HoldCo PIK Toggle notes of a Croatian consumer goods retailer. Nearly every word of that description is a flashing red light to seasoned investors. To put it a bit differently, writer and investor John Mauldin is right when he says that there is “a bubble in complacency.” Fear has effectively been banished. The members of the Fed know it. Stock traders who chase the market to new highs almost daily know it. Implied volatilities (and realized volatilities) are historically low (the VIX Index recently hit a seven-year low), and falling. The Bank for International Settlements recently cautioned that financial markets are euphoric and in the grip of an aggressive search for yield. The S&P has gone over 1,000 days without a 10% decline, according to Birinyi Associates. Dutch and French 10-year government bond yields are at 500 and 250 year lows, respectively; Spain, 225 years. Spanish debt yields were recently inside of U.S. levels. Increasingly, hopes and dreams are being capitalized as if the future is certain and nothing can go wrong, as if up cycles such as the present one don’t inevitably sow the seeds of the next decline. The European Central Bank recently cut its deposit rate to an unprecedented minus 0.1%, and Mario Draghi assured that he isn’t finished. Can this be done without consequence? Investors have become numb to risk because such policies continue, seemingly forever, and new measures (such as European and now even Chinese QE) are regularly threatened and claimed to be costless and reliably effective. We are far from convinced of this; indeed, the higher the level of valuations and the greater the level of complacency, the more there is to be concerned about. Even as reported inflation remains quite subdued, signs of incipient cost increases are increasingly evident. We are seeing them, for example, in apartment rents, construction costs, and salaries of newly minted engineering graduates and oilfield workers. Like global equity markets, credit markets have been surprisingly resilient, and our worry meter is high here, too. Ecuador recently issued $2 billion of ten-year bonds, as the market shrugged off its 2008 default. Kenya also completed a $2 billion offering, the largest ever debt sale by an African country, according to The Wall Street Journal. That offering attracted $8 billion worth of bids. In the U.S., issuance of low-grade credit is at record levels, as is covenant-lite issuance. Yields are at or near historic lows, which is especially nutty for junk credits, including the hideously risky CCC-rated issues. June CLO issuance set a record. Given changes in regulation, Wall Street has far less capital available to support the trading of this burgeoning junk issuance and the corresponding surge in debt ETFs. A sudden change in rates or sentiment could lead to serious market instability. When is harder to predict than if. While we are not predicting imminent collapse (market timing is not our thing), we are saying that a selloff, greater volatility, and investor losses would hardly be surprising from today’s levels. In markets, it’s always hard to tell, in the words of the old commercial starring Ella Fitzgerald, Is it real or is it Memorex? Is the market nearly triple its spring 2009 level because things are better, or do things feel better because the market has nearly tripled? Indeed, we can do a simple thought experiment that might be revealing: How would everything feel if the S&P 500 were suddenly cut by one-third or one-half? Would such a drop drive astonishing bargains, or would the U.S. economy soon falter, with festering problems such as unemployment, the federal, state and local deficits, the long-term fiscal situation, and the creditworthiness of most sovereigns suddenly seeming ominous? It’s not hard to reach the conclusion that so many investors feel good not because things are good but because investors have been seduced into feeling good—otherwise known as “the wealth effect.” We really are far along in re-creating the markets of 2007, which felt great but were deeply unstable when shocks started to pile up. Even Janet Yellen sees “pockets of increasing risk-taking” in the markets, yet she has made clear that she won’t raise rates to fight incipient bubbles. For all of our sakes, we really wish she would. by Guy Haselmann

Financial markets are being pushed and pulled by a variety of cross-currents. Much of the turbulence unfolding is the culmination of imbalances and tensions that have been brewing for many years. Amplified volatility in FX and commodity markets are warning signs. They appear on the cusp of spilling more broadly into other markets, exposing the full size of the iceberg. The current environment is distinct from the period of 2009-2013 when governments and central banks were quasi-coordinated in providing gargantuan amounts of stimulus, and when the geo-tensions were only chirping modestly. This year, governments and central banks have focused more generally on domestic issues. This is good in theory, but it has splintered coordination into a quasi-fracturing of the global monetary system. It should be widely known by now that past stimulus measures have ballooned sovereign debt levels and pushed official interest rates toward the zero lower bound; while other policies and regulatory changes have prodigiously distorted and manipulated asset prices and the cost of money. Stimulus, however, is no longer a one-way street. Diverging policies serve as a trigger for capital flow movements. They are shaking the foundation of capital markets, which in turn is causing second order effects like a mini-contagion. In addition, new and ever-evolving rules for investing and financial transacting have had a deleterious impact on market liquidity that will make the swishing capital flows even more magnified and treacherous for financial markets. For several decades, the global economy has benefited from globalization made possible by technological advancements. Technology has shrunk the world by being able to access more markets, and move capital and goods more efficiently. Political change (e.g., fall of the Berlin Wall) has mostly created larger and more market-friendly policies. The changing landscapes unleashed innovative capacities that typically provided great benefits and opportunities. While these factors will continue to exist, they are being met with the strongest headwinds in decades. Protectionism, nationalism, and separatist movements could begin to have great negative impacts. The social contract between people and governments has been breaking down, as witnessed in voting booths and through violent protests. Going forward, portfolios could begin to be impacted, as they activate large capital flows between sectors, securities, asset classes, and geographic regions. Investors are probably ill-equipped for a market shift from a state of low-volatility and herd-mentality investing, toward one characterized by greater bifurcation and a sustained spike in volatility. Markets have largely ignored the wars and tensions occurring in the Middle East and elsewhere. This is because, while everyone recognizes the tragedies occurring at a human level, investors realize that most disputes are far away with little effect (so far) at the investment level. In addition, troubles abroad can mean capital inflows for the US (“a cleaner dirty shirt”). A successful Scottish independence vote next week could be the game-changer. Until earlier this week, most believed there was no chance of Scotland breaking from the UK. Even after a flip in one poll showed a 1 point advantage for the “yes” campaign (for independence), most still assumed that it would not occur because they assumed that fear of what it would entail would prevail. The “no” camp fuels the fear by labelling such a scenario as an act of “madness”. However, in all likelihood, a vote for independence may not be as far-fetched and radical as the “no” campaigners suggest. The transition into independent statehood could actually go fairly smoothly with particulars negotiated in a fair and level-headed manner. There will be initial costs, but for supporters, pride trumps (unknown) costs. Fear about using the British Pound is also over-hyped as the Pound is a highly tradable freely-convertible currency. Moreover, Scotland could set up a currency board monetary authority in less than one day. The arguments and grassroots campaign of the “”yes” camp has been superior in most aspects to the disjointed fear-emphasis campaign of the “no” camp. Due to the momentum and organization of the “yes” camp, the odds of “yes” are better than even-money (even though betting organizations put it at 36%). The bottom line is that a “yes” vote is a distinct possibility; one that markets are not fully prepared for. This is because it would encourage separatist movements across Europe and beyond. As these types of uncertainties and anti-globalization aspects mount, long-dated USD-denominated Treasuries should be the marginal benefactor. In addition, tomorrow is 9/11 and the last of the August refunding auctions. The other auctions were purchased at decent levels after reasonable concessions, helping to place the securities in stronger hands. It was also a good sign that German Bunds fully regained early losses today. These are just a few reasons to own long Treasuries. Too many cross-currents and too much yield pick-up and carry makes it too soon to focus on the 2015 Fed (just yet). |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed