|

by Kevin Warsh, a former member of the Federal Reserve board, is a distinguished visiting fellow in economics at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution.

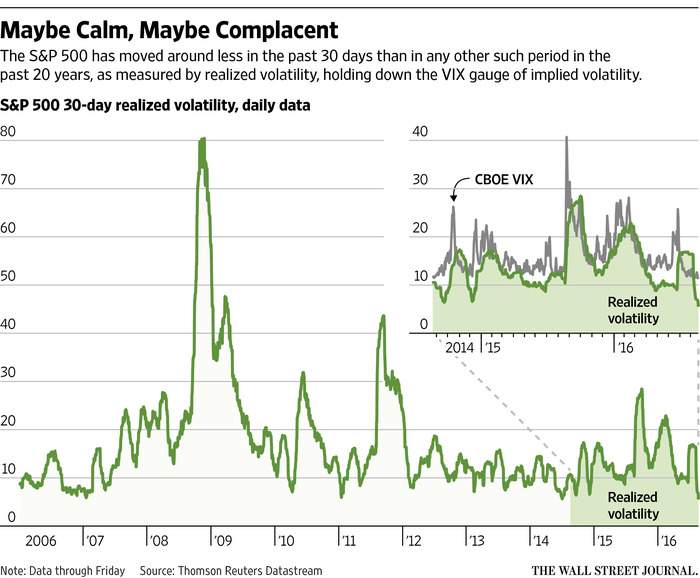

August 24, 2016 The conduct of monetary policy in recent years has been deeply flawed. U.S. economic growth lags prior recoveries, falling short of forecasts and deteriorating in the most recent quarters. This week in Jackson Hole, Wyo., the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City hosts the world’s leading central bankers and academics to consider monetary reform. The task is timely and consequential, but the Fed needs a broader reform agenda. Policy makers around the world neither predicted nor can adequately explain the reasons for current inflation readings below their targets. So it is puzzling that so many academics are pushing to raise the current 2% inflation target to a higher target of 3% or 4%. In the telling of the economics guild, the Fed’s leaders should descend from the Grand Tetons with supreme assurance that their latest monetary policy invention will remedy the economy’s ills. The Fed’s leaders should not take the bait. Raising the inflation target is a bad idea being considered at the wrong time for the wrong reasons. A new inflation target would undermine the Fed’s commitment to any policy framework. It would please the denizens of Wall Street who pine for still-looser Fed policy. And households would be understandably miffed to receive a new lecture on unconventional monetary policy—this one on the benefits of higher prices. A change in inflation targets would also add to the growing list of excuses that rationalize the economic malaise: the persistent headwinds from the crisis of the prior decade, the high-sounding slogan of “secular stagnation,” and the convenient recent alibi of Brexit. A numeric change in the inflation target isn’t real reform. It serves more as subterfuge to distract from monetary, regulatory and fiscal errors. A robust reform agenda requires more rigorous review of recent policy choices and significant changes in the Fed’s tools, strategies, communications and governance. Two major obstacles must be overcome: groupthink within the academic economics guild, and the reluctance of central bankers to cede their new power. First, the economics guild pushed ill-considered new dogmas into the mainstream of monetary policy. The Fed’s mantra of data-dependence causes erratic policy lurches in response to noisy data. Its medium-term policy objectives are at odds with its compulsion to keep asset prices elevated. Its inflation objectives are far more precise than the residual measurement error. Its output-gap economic models are troublingly unreliable. The Fed seeks to fix interest rates and control foreign-exchange rates simultaneously—an impossible task with the free flow of capital. Its “forward guidance,” promising low interest rates well into the future, offers ambiguity in the name of clarity. It licenses a cacophony of communications in the name of transparency. And it expresses grave concern about income inequality while refusing to acknowledge that its policies unfairly increased asset inequality. The Fed often treats financial markets as a beast to be tamed, a cub to be coddled, or a market to be manipulated. It appears in thrall to financial markets, and financial markets are in thrall to the Fed, but only one will get the last word. A simple, troubling fact: From the beginning of 2008 to the present, more than half of the increase in the value of the S&P 500 occurred on the day of Federal Open Market Committee decisions. The groupthink gathers adherents even as its successes become harder to find. The guild tightens its grip when it should open its mind to new data sources, new analytics, new economic models, new communication strategies, and a new paradigm for policy. The second obstacle to real reform is no less challenging. Real reform should reverse the trend that makes the Fed a general purpose agency of government. Many guild members believe that central bankers—nonpartisan, high-minded experts—are particularly well-suited to expand their policy remit. They fail to recognize that central bank power is permissible in a democracy only when its scope is limited, its track record strong, and its accountability assured. The Fed is suffering from a marked downturn in public support. Citizens are rightly concerned about the concentration of economic power at the central bank. Long after the financial crisis, the Fed holds trillions of dollars of assets that would otherwise be in private hands. And it appears to make monetary policy with the purpose of managing financial asset prices, including bolstering the share prices of public companies. With the enactment of the Dodd-Frank Act, the Fed claims the mantle of reform. It now micromanages big banks and effectively caps their rate of return. The biggest banks’ growth in market share corresponds to that of their principal regulator. They are joint-venture partners with the Fed, serving as quasi-public utilities. As the dispenser of fault and favor, the Fed is contributing to the public perception of an unfair, inequitable economic system. Real reform this is not. Most gathered in Jackson Hole will judge that the Fed’s aggressive actions are necessary and wise. Even if that were true, the Fed finds itself in an increasingly untenable position. Congress will tag the Fed for its failures, and the public will assail the Fed for favoritism for its ostensible successes. In the best of circumstances, the U.S. economy will accelerate to “escape velocity.” In that event the Fed might get the benefit of the public doubt. If, as is more likely, the economy is closer to recession than resurgence, the Fed is poorly positioned to respond with force, efficacy and credibility. The Fed is vulnerable. Its recent centennial as our nation’s central bank should not be confused with its permanent acceptance in the American political system. by James Mackintosh August 23, 2016 Calm has descended on the U.S. stock market. The past 30 days have been the least volatile of any 30-day period in more than two decades. Only five days during the most recent stretch saw the S&P 500 move by more than 0.5% in either direction, the lowest since the fall of 1995. Back then, the Federal Reserve was paused between rate cuts. This time around, a combination of the summer lull in trading and super-easy global monetary policy has helped drive volatility to levels seen only a dozen times in the past half-century. “Last week and the week before, you had to make sure your machine was actually on because it was flashing so infrequently,” said Jared Woodard, a strategist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, referring to the changes in stock prices on computer terminals. The quiet market, measured by the realized volatility—a measure of how much share prices move around—of the S&P 500, has led some to worry that a market storm may be brewing, as peaceful periods in the past have frequently ended in sharp corrections. Implied volatility, a measure of stocks’ expected future volatility and of the cost of options, has collapsed alongside realized volatility. The CBOE VIX index on Friday dropped to levels last seen in the summer of 2014—a period of calm that ended decisively with panic buying of bonds that October. The VIX, seen as Wall Street’s fear gauge, rose slightly on Monday, as the S&P fell fractionally to 2182.64. Previous periods of very low volatility were in early 2011, before the U.S.’s near-default and loss of triple-A status, and January 2007, a few months before the collapse of two Bear Stearns Cos. hedge funds marked the beginning of the credit crunch. There is more going on now than just the summer holidays. The markets are very rarely this serene, with S&P 500 realized volatility lower only a dozen times in the past half-century. In data back to 1928, this level of volatility appeared frequently only during the period from the 1951 removal of the Federal Reserve’s cap on bond yields to President Richard Nixon’s 1971 scrapping of the dollar’s link to gold. Mr. Woodard said Britain’s vote in June to leave the European Union had shocked investors, many of whom then closed their big market positions. Without many aggressive bets, there has been less need to trade on the news—and there hasn’t been much news, anyway. Investors have become more relaxed as this year’s rebound has continued, but surveys and market technical measures don’t suggest they are gripped by complacency.

Excuses can be made for the low level of the VIX, too. The implied volatility measured by the VIX should offer a premium to realized volatility, a reward for the risk taken by option sellers. Excessive complacency should show up in a shrinking risk premium, but at the moment, the gap between the VIX and realized volatility is roughly in the middle of its range from the past 20 years. The same is true for the gap between implied volatility of the next few months and further ahead. Investors seem to think volatility will pick up a bit, and again the oddity is where it stands now, not what investors are doing. “Everything feels distorted and unnatural; you know the source of that is the central banks but equally there’s nothing to stop them carrying on,” said Matt King, head of credit strategy at Citigroup. Wall Street has long seen central-bank action through the lens of the options market, since Alan Greenspan’s tenure as Fed chairman. The “Greenspan put” has under current Fed chief Janet Yellen become the “Yellen put,” named for an option used to protect against falling prices. If the Fed offers free insurance, there is no point buying your own, which ought to keep the price of puts—that is, implied volatility—down. Faith in how far central banks will protect against losses comes and goes, though. In market-speak, the Yellen put is less out of the money if a smaller price fall pushes the Fed to act. At the moment, investors seem to think the put is barely out of the money at all. The danger, then, is not so much complacency about markets, but complacency about central banks. The lesson of the past seven years is that policy makers will step in every time disaster strikes. But investors tempted to rely on the central banks should note that disasters did still strike, and markets had big falls before help arrived. The time to buy insurance is when it is cheap, and for the U.S. stock market, that is now. by Julia La Roche

Yahoo Finance August 8, 2016 Yahoo Finance: You’re the Distinguished Scientific Advisor at the hedge fund of your longtime friend Mark Spitznagel, Universa Investments, a pioneer in tail risk hedging for institutional clients. What is tail risk hedging? Nassim Nicholas Taleb: The idea at Universa is protecting clients against extreme events, those that are rare and traumatic and can threaten their survival. Counter-intuitively, by minimizing clients’ vulnerability to extreme losses through things like put options, they tend to do much better over the long run. YF: Why is it important for investors to tail risk hedge their portfolios? And how should they do this? NNT: The point is that when someone is subjected to deep losses in a large part of their portfolio, they will spend an enormous amount of their investment time rebuilding that portfolio from those losses, and any future “alpha” that is excess return from the portfolio will diverge and long term it will be much lower. Why? Because unless someone has no “uncle points,” or infinite capital, extreme loss is deterministic and does not let people emerge from it. Look at the state of under-funding of the majority of pension funds after 2008. This problem for them is only worse now. Ruin doesn’t have to be a total loss. It can be something that forces someone out of the market at the worst possible time, or, say, a 60-year old person discovering that he or she can no longer survive on future retirement income. NNT: Also, someone who minimizes their exposure to ruin by tail risk hedging can gain greater exposure to the market in other times, as they don’t have the same risk of getting stopped out as someone else so they can invest larger and for longer. Let me explain with the following example. If 100 people walk into a casino and the people who bet their money on number 27 go bust, those who bet on number 28 will not be affected. The ruin of one person does not directly affect that of others. But, if on the other hand, a person plans to walk into a casino every day for 100 days and is bust on day 27, there will be no days 28, 29, …100. So it is a mistake to look at returns of the market if you don’t have the perfect staying power, and investors should do things like tail risk hedging to ensure the highest certainty of survivorship. What Mark is doing at Universa is just that: providing staying power and robustness for clients. YF: You and Spitznagel have been doing this for a long time. What have you learned? NNT: One should stay consistent, keep an iron discipline. Mark and I have been protecting against extreme risks for nearly twenty years together. During that time, we’ve seen tail hedgers come and go by following whims and not truly focusing long term on hedging. Universa is a true “hedge” fund, as it lowers portfolio uncertainty rather than adding to it. One needs to work very, very hard at calibrating the right kind of exposure and making sure it delivers a payout in a true crash, just like Universa did in 2008, while keeping costs minimal otherwise. Refining both sides of that pendulum is the most important, and it creates its own alpha for investors. Also one can’t view hedging in isolation. The portfolio package is what matters, and investors need to know you can’t achieve one without the other. YF: What are the biggest risks out there right now? NNT: The fact that the world, as a result of quantitative easing, has seen an asset inflation that benefited the uber-rich, and that nothing has been cured. One cannot cure debt with debt, by transferring from private to public sectors. The markets will ultimately crash again, although this time it will hurt a lot more people. YF: A lot of people throw around the phrase ‘black swan’ haphazardly. What do people most commonly get wrong when talking about black swans? NNT: They don’t get that what matters is to be protected against those tail risks that matter, something easier to do than trying to predict them. The idea is to focus on portfolio robustness rather than forecasts. YF: Finally, you’re very active on social media — Twitter and Facebook. What do you think the role of social media plays in politics, the economy and the markets? NNT: Social media allowed me to go direct to the public and bypass the press, an uberization if you will, as I skip the intermediary. I do not believe that members of the press knows their own interests very well. I noticed that journalists try to be judged by other journalists and their community, not by their readers, unlike writers. This cannot be sustainable. Also, if you say it the way it is, people trust you. The central modus operandi is to avoid marketing: social media is a way to test ideas and work in progress and give-and-take to and from the readers. by Satyajit Das - author of A Banquet of Consequences, published in North America as The Age of Stagnation

Financial Times August 1, 2106 Since 2008, total public and private debt in major economies has increased by over $60tn to more than $200tn, about 300 per cent of global gross domestic product (“GDP”), an increase of more than 20 percentage points. Over the past eight years, total debt growth has slowed but remains well above the corresponding rate of economic growth. Higher public borrowing to support demand and the financial system has offset modest debt reductions by businesses and households. If the average interest rate is 2 per cent, then a 300 per cent debt-to-GDP ratio means that the economy needs to grow at a nominal rate of 6 per cent to cover interest. Financial markets are now haunted by high debt levels which constrain demand, as heavily indebted borrowers and nations are limited in their ability to increase spending. Debt service payments transfer income to investors with a lower marginal propensity to consume. Low interest rates are required to prevent defaults, lowering income of savers, forcing additional savings to meet future needs and affecting the solvency of pension funds and insurance companies. Policy normalisation is difficult because higher interest rates would create problems for over-extended borrowers and inflict losses on bond holders. Debt also decreases flexibility and resilience, making economies vulnerable to shocks. Attempts to increase growth and inflation to manage borrowing levels have had limited success. The recovery has been muted. Sluggish demand, slowing global trade and capital flows, demographics, lower productivity gains and political uncertainty are all affecting activity. Low commodity, especially energy, prices, overcapacity in many industries, lack of pricing power and currency devaluations have kept inflation low. In the absence of growth and inflation, the only real alternative is debt forgiveness or default. Savings designed to finance future needs, such as retirement, are lost. Additional claims on the state to cover the shortfall or reduced future expenditure affect economic activity. Losses to savers trigger a sharp contraction of economic activity. Significant writedowns create crises for banks and pension funds. Governments need to step in to inject capital into banks to maintain the payment and financial system’s integrity. Unable to grow, inflate, default or restructure their way out of debt, policymakers are trying to reduce borrowings by stealth. Official rates are below the true inflation rate to allow over-indebted borrowers to maintain unsustainably high levels of debt. In Europe and Japan, disinflation requires implementation of negative interest rate policy, entailing an explicit reduction in the nominal face value of debt. Debt monetisation and artificially suppressed or negative interest rates are a de facto tax on holders of money and sovereign debt. It redistributes wealth over time from savers to borrowers and to the issuer of the currency, feeding social and political discontent as the Great Depression highlights. The global economy may now be trapped in a QE-forever cycle. A weak economy forces policymakers to implement expansionary fiscal measures and QE. If the economy responds, then increased economic activity and the side-effects of QE encourage a withdrawal of the stimulus. Higher interest rates slow the economy and trigger financial crises, setting off a new round of the cycle. If the economy does not respond or external shocks occur, then there is pressure for additional stimuli, as policymakers seek to maintain control. All the while, debt levels continue to increase, making the position ever more intractable as the Japanese experience illustrates. Economist Ludwig von Mises was pessimistic on the denouement. “There is no means of avoiding the final collapse of a boom brought about by credit expansion,” he wrote. “The alternative is only whether the crisis should come sooner as a result of a voluntary abandonment of further credit expansion, or later as a final and total catastrophe of the currency system involved.” by Bill Gross

Janus Capital August 3, 2106 When does our credit-based financial system sputter/break down? When investable assets pose too much risk for too little return. Not immediately, but at the margin, low/negative yielding credit is exchanged for figurative and sometimes literal gold or cash in a mattress. When it does, the system delevers as cash at the core, or real assets like gold at the risk exterior, become the more desirable assets. Central banks can create bank reserves, but banks are not necessarily obliged to lend it if there is too much risk for too little return. The secular fertilization of credit creation may cease to work its wonders at the zero bound, if such conditions persist. Can capitalism function efficiently at the zero bound? No. Low interest rates may raise asset prices, but they destroy savings and liability based business models in the process. Banks, insurance companies, pension funds and Mom and Pop on Main Street are stripped of their ability to pay for future debts and retirement benefits. Central banks seem oblivious to this dark side of low interest rates. If maintained for too long, the real economy itself is affected as expected income fails to materialize and investment spending stagnates. Can $180 billion of monthly quantitative easing by the ECB, BOJ, and the BOE keep on going? How might it end? Yes, it can, although the supply of high quality assets eventually shrinks and causes significant technical problems involving repo, and of course negative interest rates. Remarkably, central banks rebate almost all interest payments to their respective treasuries, creating a situation of money for nothing — issuing debt for free. Central bank "promises" of eventually selling the debt back into the private market are just that — promises/promises that can never be kept. The ultimate end for QE is a maturity extension or perpetual rolling of debt. The Fed is doing that now but the BOJ will be the petri dish example for others to follow, if/ when they extend maturities to perhaps 50 years. When will investors know if current global monetary policies will succeed? Almost all assets are a bet on growth and inflation (hopefully real growth) but in its absence at least nominal growth with some inflation. The reason nominal growth is critical is that it allows a country, company or individual to service their debts with increasing income, allocating a portion to interest expense and another portion to theoretical or practical principal repayment via a sinking fund. Without the latter, a credit-based economy ultimately devolves into Ponzi finance, and at some point implodes. Watch nominal GDP growth. In the U.S. 4-% is necessary, in Euroland 3-4%, in Japan 2-3%. What should an investor do? In this high risk/low return world, the obvious answer is to reduce risk and accept lower than historical returns. But don't you have to put your money somewhere? Yes, of course, except markets offer little in the way of double digit returns. Negative returns and principal losses in many asset categories are increasingly possible unless nominal growth rates reach acceptable levels. I don't like bonds; I don't like most stocks; I don't like private equity. Real assets such as land, gold, and tangible plant and equipment at a discount are favored asset categories. But those are hard for an individual to buy because wealth has been "financialized". How about Janus Global Unconstrained strategies? Much of my money is there. Reuters

August 2, 2106 Aug 2 Bond markets across the world are at risk to lose up to $3.8 trillion if bond yields suddenly surge back to their 2011 levels from their current historic lows, Fitch Ratings said on Tuesday. European and Japanese government bond yields have been in negative territory due to their central banks' adaptation of negative rate policies and expansion of bond purchases in 2016. Longer-dated U.S. Treasury yields reached record lows in July in a global scramble for higher-yielding sovereign debt. "As rates hit record lows, investors face growing interest rate risk. A hypothetical rapid rate rise scenario sheds light on the potential market risk faced by investors with high-quality sovereign bonds in their portfolios," Fitch Ratings said in a statement. In its analysis, a hypothetical rapid reversion of yields to 2011 levels for $37.7 trillion worth of investment-grade sovereign bonds could result in market losses of as much as $3.8 trillion, it said. From July 2011 to July 2016, the median yield on the 10-year government bonds among 34 countries fell by 2.70 percentage points. The median yield on one-year debt declined by 1.76 points, Fitch said. On July 15, there were $11.5 trillion worth of government bonds globally which offered negative yields, which were less than the $11.7 trillion on June 27. The sum of negative-yielding bonds decreased due to the yen's rally against the dollar and a rise in Japanese government yields, according to Fitch. |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed