|

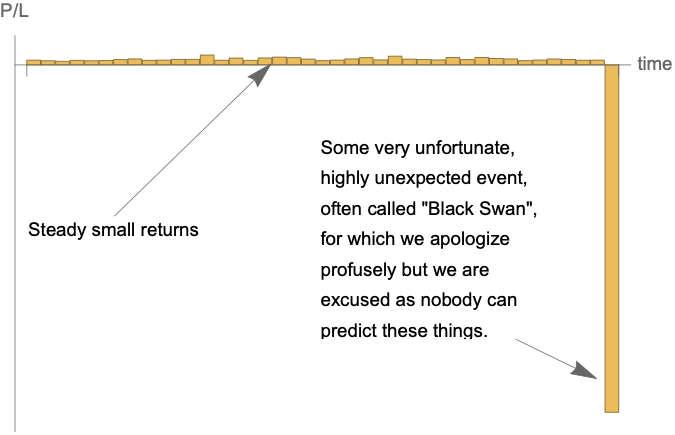

The Government is Bailing Out Investors & Managers Not You by Nassim Nicholas Taleb with Mark Spitznagel) Medium.com March 26, 2020 The U.S. government is enacting measures to save the airlines, Boeing, and similarly affected corporations. While we clearly insist that these companies must be saved, there may be ethical, economic, and structural problems associated with the details of the execution. As a matter of fact, if you study the history of bailouts, there will be. The bailouts of 2008–9 saved the banks (but mostly the bankers), thanks to the execution by then-treasury secretary Timothy Geithner who fought for bank executives against both Congress and some other members of the Obama administration. Bankers who lost more money than ever earned in the history of banking, received the largest bonus pool in the history of banking less than two years later, in 2010. And, suspiciously, only a few years later, Geithner received a highly paid position in the finance industry. That was a blatant case of corporate socialism and a reward to an industry whose managers are stopped out by the taxpayer. The asymmetry (moral hazard) and what we call optionality for the bankers can be expressed as follows: heads and the bankers win, tails and the taxpayer loses. Furthermore, this does not count the policy of quantitative easing that went to inflate asset values and increased inequality by benefiting the super rich. Remember that bailouts come with printed money, which effectively deflate the wages of the middle class in relation to asset values such as ultra-luxury apartments in New York City. If It’s Bailed Out, It’s a Utility First, we must not conflate airlines as a physical company with the financial structure involved. Nor should we conflate the fate of the employees of the airlines with the unemployment of our fellow citizens, which can be directly compensated rather than indirectly via leftovers of corporate subsidies. We should learn from the Geithner episode that bailing out individuals based on their needs is not the same as bailing out corporations based on our need for them. Saving an airline, therefore, should not equate to subsidizing their shareholders and highly compensated managers and promote additional moral hazard in society. For the very fact that we are saving airlines indicates their role as utility. And if as such they are necessary for society, then why do their managers have optionality? Are civil servants on a bonus scheme? The same argument must also be made, by extension, against indirectly bailing out the pools of capital, like hedge funds and endless investment strategies, that are so exposed to these assets; they have no honest risk mitigation strategy, other than a trained naïve reliance on bailouts or what’s called in the industry the “government put”. Second, these corporations are lobbying for bailouts, which they will eventually get thanks to the pressure they can exert on the government via lobby units. But how about the small corner restaurant ? The independent tour guide ? The personal trainer? The massage professional? The barber? The hotdog vendor living from tourists near the Met Museum ? These groups cannot afford lobbyists and will be ignored. Buffers Not Debt Third, as we have been warning since 2006, companies need buffers to face uncertainty –not debt (an inverse buffer), but buffers. Mother nature gave us two kidneys when we only need about a portion of a single one. Why? Because of contingency. We do not need to predict specific adverse events to know that a buffer is a must. Which brings us to the buyback problem. Why should we spend taxpayer money to bailout companies who spent their cash (and often even borrowed to generate that cash) to buy their own stock (so the CEO gets optionality), instead of building a rainy day buffer? Such bailouts punish those who acted conservatively and harms them in the long run, favoring the fool and the rent-seeker. Not a Black Swan Furthermore, some people claim that the pandemic is a “Black Swan”, hence something unexpected so not planning for it is excusable. The book they commonly cite is The Black Swan (by one of us). Had they read that book, they would have known that such a global pandemic is explicitly presented there as a white swan: something that would eventually take place with great certainty. Such acute pandemic is unavoidable, the result of the structure of the modern world; and its economic consequences would be compounded because of the increased connectivity and overoptimization. As a matter of fact, the government of Singapore, whom we advised in the past, was prepared for such an eventuality with a precise plan since as early as 2010. Reuters by Svea Herbst-Bayliss, Lawrence Delevingne March 18, 2020 The New York hedge fund manager, seasoned by past financial crises and spooked by seemingly endless quarters of ever-higher markets, had for years set up for financial calamity, even if it meant sometimes poor returns. When panic over the coronavirus spread to global financial markets in late February, Weinstein swung into action. Glued to a battery of computer screens to transact in three time zones for 15 hours a day, the former Deutsche Bank AG trader scored on bond and credit default swap-related bets and cashed in on old insurance-like derivatives products for a steep market decline, according to people who know him. By Friday, Weinstein had produced the best returns in $2.7 billion Saba Capital Management LP's history. Its Tail Fund gained more than 175% through March 13; other Saba funds gained between 53% and 67%, according to a client letter reviewed by Reuters here “I certainly did not expect it to come from a virus, but I have had the conviction – for a long time – that investors needed to be ready for an extreme market decline,” Weinstein wrote in the letter that was sent to investors on Sunday. A spokesman for Saba declined to comment. Saba is among a small group of firms that have scored major returns for clients in recent weeks through so-called tail risk products. The CBOE Eurekahedge Tail Risk Hedge Fund Index gained 14% in February alone and, combined with estimated March performance, is likely up between 32% and 41% for the year, according to a Eurekahedge analysis. Goldman Sachs Group Inc estimates that the average stock-focused hedge fund, by comparison, is down about 14% for the year through March 17, compared with a 25% benchmark stock market loss. Tail products - including hedge funds, customized portfolios and exchange traded funds (ETFs) - typically use credit default swaps, stock options and other derivatives to profit from severe market dislocations. Generally they are cheap bets for a big, long-shot payoff that otherwise are a drag on the portfolio, much like monthly insurance policy payments. Such funds have been around since the 2008 financial crisis, but they gained limited traction by producing mixed returns during the bull market. ‘MULTIPLES’ OF 1,000% A client of Universa Investments LP, a $4.1 billion [correction: $13 billion - Lionscrest] Miami-based risk mitigation specialist, saw money allocated to the firm’s tail hedging strategy gain around 1,000% in February and “multiples” of that in March, according to Claude Bovet of Lionscrest Capital. That implies a gain of at least 3,000%; the net return on Lionscrest’s total portfolio was not available. “This has been a great period for us and our clients,” Universa chief investment officer Mark Spitznagel said via a spokesman, who declined to comment on performance. Other big winners include Capstone Investment Advisors, whose $7 billion firm runs tail risk strategies for clients that have gained 280% this year through Monday, according to a person familiar with the returns; 36 South Capital Advisors’ volatility strategy, which rose 35% over January and February, according to data from Societe Generale; and the $126 million Cambria Tail Risk ETF, which is up about 25% this year through Tuesday. “Our tail risk products are doing exactly what they are designed to do,” said Meb Faber, chief investment officer at El Segundo, California-based Cambria Investment Management LP. Representatives for Capstone and 36 South declined to comment. These types of portfolios are always popular during a crisis but when no next terrible event happens, investment managers and boards often lose patience and exit, complaining of low returns or losses. Last year, when the S&P500 stock index gained 30%, the benchmark CBOE Eurekahedge index lost 10.4%. The gains this year are likely to spur renewed interest. Weinstein’s Saba has seen $500 million come in this year and told investors that he will limit inflows into his funds to an aggregate of $1 billion for 2020. Weinstein said Saba was now “finding extraordinary new investments” amid the turmoil. Winning managers were mindful that their gains came as a result of a health crisis that has sickened nearly 200,000 people around the world and killed 7,500 as of Wednesday, according to the World Health Organization (as referenced here). “We provide protection, an effective safe haven,” said Universa’s Spitznagel. “But we certainly didn’t need nor want this tragedy to happen.” ‘Black Swan’ fund Universa made huge gains in February as markets swooned from coronavirus risk without making any assumptions about the epidemic

by Spencer Jakab Updated March 4, 2020 8:02 am ET Imagine that an investor knew back in early December that a deadly coronavirus was spreading in Wuhan, China, that could become a pandemic. Or imagine that he at least heard and heeded the warning by the tragically muzzled Dr. Li Wenliang at the end of that month. Acting on that information by, say, shorting the highflying Nasdaq Composite might have sounded like a good idea, but the results would have been disastrous. By the time the index hit its intraday record on Feb. 19, a forewarned investor would have trailed that index by about 30 and 20 percentage points, respectively. Yet one fund that makes its living protecting portfolios from such events may have reaped a bonanza in February without such insights. Universa, managed by Mark Spitznagel, a protégé of “The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable” author Nassim Nicholas Taleb, managed a little over $4 billion in assets as of the end of 2018. Claude Bovet, founder of Lionscrest Capital and a long time investor in the fund, estimates that Universa’s tail risk hedging strategy, representing part of its capital, earned more than 1,000% in a matter of days. “It was a great month for us,” says Mr. Spitznagel, who declined to disclose a dollar figure on those gains. He did point out, though, that the fund’s positions are “convex to the market.” In other words, its strategy of using options and similar instruments can register profits that escalate in much more than a linear fashion, suggesting a handsome payoff indeed. Back in August 2015 the fund made over $1 billion, or 20%, in a single day when the Dow had what was then its largest ever intraday plunge of over 1,000 points, ending down by 588 points. The index lost 3,583 points last week—its worst such period since the financial crisis and sharpest ever drop from a peak. Yet, even as patients were succumbing to the illness in Wuhan, the cost of placing bets in the run-up to the selloff was extremely low as represented by the Cboe Volatility Index, or VIX. The so-called fear gauge, it represents the cost of purchasing options as expressed by the implied volatility embedded in their prices. Universa hedged without timing the market or taking a risk, which holds a lesson about risk, reward and complacency. While many reasonable investors were tempted to sell tech stocks or bet against them—2,000 people had died by the day they peaked—Universa ignored the headlines and focused only on what the numbers said. They told it that insurance was cheap. “If you have a position that can lose 1 to make 100, like Universa’s tail hedge at any point in time, you don’t care about your timing of a market crash, you just don’t want to miss it,” says Mr. Spitznagel. Buying protection in such a fund is akin to purchasing insurance from an optimistic underwriter—writing small monthly checks and very rarely receiving a big one in return. Returns can be negative for years. Yet even during a mostly excellent run for U.S. stocks, the strategy trounced the stock market in its first 10 years through February 2018, according to a leaked client letter. Mr. Spitznagel, who acknowledges spending all of his time “thinking about looming disaster,” expressed no view on what the impact of the Covid-19 epidemic might now be on stock prices. Even so, his advice to those with a bearish inclination is hardly uplifting: “For people who are worried about having missed it, this selloff has only taken back a few months of gains. I expect a true crash to take back a decade.” |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed