|

We tend to feature John Hussman in these pages because his empirically-derived and rigorous analysis augmented by insights developed from extensive experience in managing money (in contrast to talking-heads with "no skin in the game", to quote Taleb) necessitate serious consideration. Tail-hedging is not a perma-bear strategy, nor is it effective only in doomsday scenarios; on the contrary, it is a hedging strategy that combines a bullish emphasis (by maximising positive outcomes through the elimination of extreme negative ones) with robust risk management (not reliant on theories or models). In this context, we do not quote Hussman because he is a perma-bear (he is not), but because his insights are instructive in maximising the potential to earn returns over a full market cycle. It just so happens that in the current market, not only are his indicators flashing red-alert but his instincts derived from extensive experience scream "hedge!" (Hussman employs a protective put option strategy in his funds). And with good reason, as he explains in his recent weekly commentary.

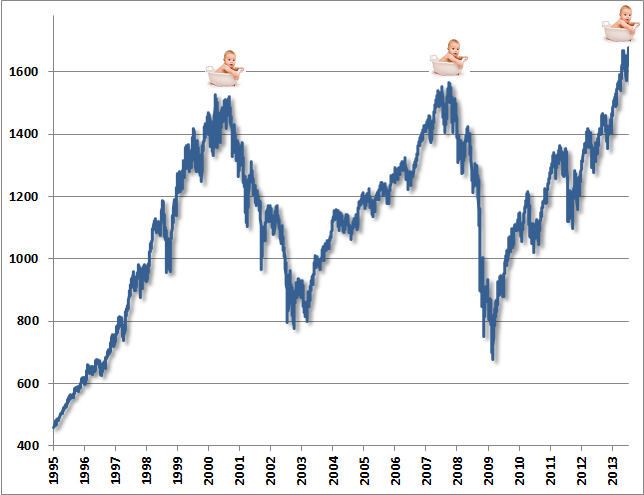

----- July 29, 2013 Baked In The Cake (click to access full report) John P. Hussman, Ph.D. Excerpts: --- “The U.S. equity market is now in the third, mature, late-stage, overvalued, overbought, overbullish, Fed-enabled equity bubble in just over a decade. Like the 2000-2002 plunge of 50%, and the 2007-2009 plunge of 55%, the current episode is likely to end tragically. This expectation is not a statement about whether the market will or will not register a marginal new high over the next few weeks or months. It is not predicated on the question of whether or when the Fed will or will not taper its program of quantitative easing. It is predicated instead on the fact that the deepest market losses in history have always emerged from an identical set of conditions (also evident at the pre-crash peaks of 1929, 1972, and 1987) – namely, an extreme syndrome of overvalued, overbought, overbullish conditions, generally in the context of rising long-term interest rates.” --- “Despite individual features that convinced investors in each instance that “this time is different”, the corresponding handful of truly breathtaking market losses in history have a single source: the willingness of investors to forego the need for a risk premium on securities that have always required one over time. Once the risk premium is beaten out of stocks, there is no way out, and nothing that can be done about it. Poor subsequent returns, market losses, and the associated destruction of financial security (at least for the bag-holders) are already baked in the cake. This should have been the lesson gleaned from the period since 2000, but because it remains unlearned, it will also become the lesson of the coming decade. “ --- “With respect to the present, mature, overvalued, speculative half-cycle, I don't expect this cycle to be completed with a 20% loss, or a 25% loss, but instead a loss in the 40-55% range. Again - this isn't even a dire forecast. A 40% market loss is the central expectation.” --- “The Shiller P/E is now 24.4, about the same level as August 1929, higher than December 1972, higher than August 1987, but less extreme than the level of 43 that was reached in March 2000 (a level that has been followed by more than 13 years of market returns within a fraction of a percent of the return on Treasury bills – and even then only by revisiting significantly overvalued levels today). The Shiller P/E is presently moderately below the level of 27 at the October 2007 market peak.” --- “In short, we have one of the most overvalued, overbought, overbullish equity markets in history, but one where investors are under the illusion that stocks are appropriately priced, because they are being sold a valuation benchmark (forward operating earnings) that reflects profit margins 70% above historical norms – a direct result of unsustainably large deficits in combined government and household savings.” --- “Let’s be clear about something. Since 2000, the S&P 500 has achieved an average annual total return barely higher than 2% annually, and even then only by re-establishing overvalued levels at present. If there was any period since the Depression to be concerned about valuations and market risk, this has been the time – and it continues.” --- “Frankly, I still view QE as a confidence game that has no financial mechanism except to make investors uncomfortable holding Treasury bills, and no theoretically valid or empirically supported transmission mechanism to the real economy at all. I’m both surprised and a little bit disappointed that investors have again placed their confidence and financial security on what is the economic equivalent of a cheap parlor trick.” --- “For those who trust my judgment, I can tell you not only that we are far, far more inclined to encourage constructive and aggressive investment exposures over the course of the complete market cycle than casual observers may recognize – but I will also tell you that the stock market – here and now – is at a far, far more dangerous point in that cycle than investors can imagine.” --- “A final note – be aware that overvalued, overbought, overbullish periods often feature what I’ve called “unpleasant skew.” As I noted before significant corrections in 2010 and 2011: “If you look at overvalued, overbought, overbullish, hostile yield conditions of the past, you'll find that the most likely market outcome, in terms of raw probability, is a continued tendency for the market to achieve successive but slight marginal new highs. While this movement tends to be fairly muted in terms of overall progress, it can be somewhat excruciating for investors in a defensive position, because the market tends to pull back by a only a few percent, followed by bursts that recover that lost ground and achieve minor but widely celebrated new highs. That is the ‘unpleasant’ part. The ‘skew’ part is that although the raw probability tends to favor slight successive new highs, the remaining probability tends to feature nearly vertical drops, typically well over 10% over a period of weeks.”” Nassim Taleb, author of the new book, Antifragile, praises volatility and criticizes those who would artificially dampen it at great unseen cost. Taleb writes: "Stifling natural fluctuations masks real problems, causing the explosions to be both delayed and more intense when they do take place. As with the flammable material accumulating on the forest floor in the absence of forest fires, problems hide in the absence of stressors and the resulting cumulative harm can take on tragic proportions. And yet our economic policy makers have often aimed for maximum stability, even attempting to eradicate the business cycle."

There is no free lunch in economics: if governments could print or borrow money in astronomical amounts without any major adverse consequences, why wouldn't they always do this, forever avoiding downturns while their countries bask in the sunshine of limitless prosperity? Indeed, it seems clear that prior misplaced confidence in the Fed contributed greatly to years of complacency that turned the 2008 downturn into a full-blown crisis. Of course there will be a price to pay for today's policy excesses—an equal and opposite reaction. We just haven't seen it yet. Will it take the form of a collapse of the dollar and the end of dollar hegemony, high interest rates, failed auctions of U.S. government securities and runaway inflation, a wrenching and protracted downturn requiring exceptional sacrifice, or something else'? We will find out soon enough. Implicit is that a 30% market drop might follow a full reversal of QE policies. But equity investors who have embraced a momentum strategy are ill-prepared for a policy change that could reverse the market's artificial gains. What will happen when the Fed declares, as it someday must, that the era of artificially low interest rates is at an end? Or if another serious crisis—economic, political, international—materializes and governments have insufficient ammunition to intervene? The content, though not the timing, of the next chapter in market history is quite predictable. Few will say they saw it coming, though, in fact, everyone could have seen it if they had only chosen to take off their blinders and look. Leverage is always a double-edged sword, and in 2007 excessive leverage at all levels of the economy had eroded our nation's margin of safety. When things went wrong in 2008, we' had nothing to fall back on. There was no room for error, little cushion to give us time to refocus and rebuild. Today, with massive deficits and even higher government debt, we have less margin for error than we did four years ago. What might we do instead of today's unsuccessful, misguided, and dangerous programs? Jim Grant, in a CNBC interview several months ago, had one suggestion: perhaps we should try capitalism. Let's allow markets to operate freely; let's allow the invisible hand to work its magic; let's once again permit failure. A juiced-up stock market is seen as stability? A policy that creates such "stability" and from which there is no apparent exit is seen as wise and even successful? And the policy must be continued because it was so ill-conceived that it cannot be ended? The Greenspan-Bernanke put exists because even the hint of a minor economic downturn has for decades been viewed by government officials as a crisis so extreme that it must be warded off at all costs. Thus, we have created the twin illusions of limitless prosperity and the taming of economic volatility at the high cost of ever-expanding deficits, overleverage in the consumer and government sectors, extreme moral hazard, and episodic market meltdowns. Economist Hyman Minsky has posited the simple but brilliant notion that stability leads to instability. Low economic volatility, by enticing lenders to make low-cost loans available to historically risky borrowers and by encouraging borrowers to take on ultimately unaffordable debts, creates conditions ripe for destabilizing credit hubbies to form, expand, and eventually collapse. While zero rate policy is somewhere between financial catnip and heroin to investors, one of the most powerful concepts in finance is reversion to the mean, Jeremy Grantham is perhaps the most articulate proponent of this concept. Across all markets and asset classes, valuations eventually revert to the mean. While you can never tell in advance precisely when they will end, all bubbles, which he defines as valuations more than two standard deviations above trend-line, eventually reverse. The psychology that allows bubbles to form always breaks, sometimes on a dime. This is not just theoretical; looking back over the centuries, Jeremy has the data that prove it. The daily cheerleading pundits exult at rallies and record highs and commiserate over market reversals ; viewers get the impression that up is the only rational market direction and that selling or sitting on the sidelines is almost unpatriotic…. in a world where differences between investing and speculation are frequently blurred, the nonsense on the financial cable channels only compound the problem. Alan Greenspan's mantra was that the Fed couldn't possibly identify financial bubbles before they burst; it is better for the government to clean them up after they implode. I couldn't disagree more strongly. Asymmetrically truncating investors' downside risk, without an equal and opposite intervention to limit bubble-like upside, is highly pernicious. For decades, financial institutions and individual investors have come to expect limited financial market downside due to such government interventions. With downside artificially constrained and upside driven by the forces I've described, a purported era of "Great Moderation" prevailed through 2007 - one of low volatility and shallow downturns. Such conditions were used to justify increasingly lax lending standards (because few loans went bad amidst steadily rising asset values) and, because of the availability of credit and its low cost, a monumental expansion of leverage. All these things that propel markets higher, that limit downside volatility, that drive perceptions of risk lower, sow the seeds for periodic collapses such as the one in 2008, that are far more devastating than would happen otherwise. Two problems are upon us at once: short-term stimulus that is unaffordable and unsustainable entitlements that must be reined in. But restoring fiscal sanity by reducing spending and raising receipts will be bad in the short run for the economy and financial markets. What Treasury official or politician would want the cash spigot turned off before a recovery is certain? Recipients of government handouts would grumble at the prospective termination of government policies that offer them outsized benefits. We've seen what that looks like in cities across Europe. Which explains the endless chorus of "but not yet." One sees this in editorials and commentaries, such as the ones saying it's time to close down bankrupt Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, but not yet, because doing so might harm the housing market. There will never be a good time to end housing support programs, reverse quantitative easing policies, or reduce massive budget deficits—because doing so will restrict growth and depress stock prices. Nor will there be a good time to cut entitlement programs or to solve Social Security or Medicare underfunding. Most will always agree the stimulus cannot go on forever, that excessive entitlements must be reined in, "but not yet" Government effort to pump stocks higher is expensive and distortive. And if the impact will only be ephemeral, if what goes up is certain to come back down, then the consequence is bound to be increased volatility, more financial catastrophe, and possibly an endless cycle of propping up followed by collapse, perhaps with greater and greater amplitude and, looking back, ultimately without any purpose other than as a short-term palliative for psychological or political purposes. Government manipulation of stock prices to unnaturally high levels is economically destructive because the wrong market signals are sent and society's resources are potentially massively misallocated. It also at least temporarily accentuates wealth disparities that undermine social cohesion. Indeed, they may have coaxed out additional production of assets already in excess supply, such as housing and office building which, if truly unneeded, would only exacerbate losses in the next economic downturn. Worse still—and this is one of my great fears--I'm certain that in the minds of Fed and Treasury officials, government actions since 2008 have been a great success and as such will figure prominently in the playbook they will leave on the shelf for their successors There is no precise level where debt becomes excessive. It depends on the vicissitudes of investors and the vagaries of the markets. When asked how he went bankrupt, Hemingway's character, Mike Campbell, in The Sun Also Rises, answered, "Gradually, and then suddenly." An unknowable tipping point looms over the horizon. When we reach it outsiders and U.S. citizens alike will become increasingly suspicious of our creditworthiness causing interest rates to rise and the dollar to decline. No one knows precisely how much debt is too much, or at what moment the tipping point will be reached. It's like driving a car with a faulty navigation system along a steep mountain road on a moonless night. Sooner or later, you're going to plummet over the edge. By the time we reach that point, it will likely be too late. We borrow heavily, spend a lot but invest very little, fail to address long-term problems allowing them to fester and compound, and leave ourselves at the mercy of creditors with little or no room for error. Should disaster suddenly strike—an act of God, a war, another Wall Street or financial market implosion—we would be in great trouble. No rational investor would want to rely on prayer or divine intervention for their future viability. No country should, either. I certainly don't think we should feel good because we are less of a basket case than Europe or Japan. Getting our affairs in order to where we once again build in a margin of safety will take considerable time. We must get started right away. These are exceptional times; tail-risk option pricing is reflecting extreme complacency as market participants are put to sleep by the Bernanke Put. Hussman once again provides timely insights and continues with our series of posts into hidden extreme tail risk currently embedded in financial markets. ----- July 15, 2013 Rock-A-Bye Baby John P. Hussman, Ph.D. Rock-a-bye baby On the treetop When the wind blows The cradle will rock When the bough breaks The cradle will fall And down will come baby Cradle and all I’ve always thought that singing “Rock-a-bye baby” offers a bizarre lesson to our young, encouraging them to be lulled gently to sleep by describing a scene that should have them wide-eyed with terror. Let’s get this straight. You’ve got this baby, in a cradle, teetering on some fractured bough, at the top of a tree, complacently rocking with each breeze, with baby, cradle, and all facing an inevitable disaster that’s inherent in the situation itself. And everyone is OK with this. You can see why I chose this song for this week’s market comment. It’s important to start this discussion by emphasizing that we align our outlook with the prevailing evidence at each point in time. So for example, if a meaningful retreat in valuations was followed by a firming in our broad measures of market internals, our views would become at least moderately constructive even if stocks were still overvalued from a cyclical or secular standpoint. We remain flexible to new evidence. Given the present evidence, however, my real concern is that much like the rolling tops of 2000 and 2007, each pleasant breeze here lulls investors into complacency – but in the face of overvalued, overbought, overbullish conditions that, from a cyclical and secular standpoint, should probably have them wide-eyed with terror (see Closing Arguments for a broad review of our concerns here). We can’t rule out that the bough will sway for a while longer despite the weight, but we won’t embrace the situation by putting our own baby on the twigs. It’s quite crowded up there already. To continue reading, click here.

Continuing with commentary on the current high level of tail-risk in financial markets, John Hussman provides a compelling insight: "Market crashes are always driven by a spike in risk premiums from previously inadequate levels".

----- Weekly Market Comment All of the Above By John P. Hussman, Ph.D. July 1, 2013 Excerpt: One of the results of writing on a wide range of economic and financial topics is that investors sometimes assume that my market views are dependent on some particular data point or Fed decision. Current events are interesting in the sense that they can affect the various measures that we use to classify market conditions, but those measures are actually what matter most because they can be tested and validated across history. In a nutshell, here are some of the basic conditions that I believe are relevant for risk-taking in stocks, and the order in which I tend to consider them: First, an overvalued, overbought, overbullish syndrome of conditions has historically trumped all other considerations – on average – particularly when yields are rising and price momentum has flattened. Market crashes are always driven by a spike in risk premiums from previously inadequate levels. Never forget that. When risk premiums are squeezed to deeply depressed levels (as QE has done) and upward pressures on those risk premiums then emerge, markets collapse. Absent that syndrome, favorable market internals and trend-following conditions generally dominate other considerations. Valuations are the primary determinant of long-term returns, but over shorter horizons, valuations are essentially a “modifier” – meaning that the stocks typically enjoy the strongest gains of the market cycle when broad market action is positive and favorable valuations provide a tailwind. The lesson from Depression-era data isn’t different in this regard. Rather, Depression-era data teaches that neither favorable trend-following measures (which were heavily whipsawed) nor favorable valuations were enough to avoid deep losses until they were confirmed by positive divergences in market internals and other measures. I think that’s probably what Jesse Livermore had in mind when he wrote “It isn’t as important to buy as cheap as possible as it is to buy at the right time.” Livermore also observed that his worst losses were the result of lapses in the discipline of investing “only when I was satisfied that precedents favoured my play.” Few things in finance are truly unprecedented – including the Depression and QE – once you quantify how they exert their influence on the variables that determine prices (cash flows, growth rates, risk-free discount rates and risk premiums). In the absence of favorable market internals, easy monetary policy is far less helpful than investors believe. From an asset allocation perspective, even simple trend-following methods have performed far better than following monetary policy. QE has undoubtedly complicated the period since 2010, but a good part of that difficulty was actually during periods when market internals were favorable while an overvalued, overbought, overbullish syndrome was absent. Most of the remaining difficulty has been over the past year, as stocks have advanced despite a persistent overvalued, overbought, overbullish syndrome – contrary to average historical outcomes. Then again, I suspect that it will be striking how quickly those gains are surrendered if market internals remain broken. What’s disturbing, if you actually examine the historical evidence, is that while favorable market action tends to be favorable regardless of the monetary policy stance, unfavorable market action coupled with easy money is actually more hostile than unfavorable market action coupled with tight money. As I noted in Following the Fed to 50% Flops, “Strikingly, the maximum drawdown of the S&P 500, confined to periods of favorable monetary conditions since 1940, would have been a 55% loss. This compares with a 33% loss during unfavorable monetary conditions. This is worth repeating – favorable monetary conditions were associated with far deeper drawdowns.” I’ll end by repeating what I view as the most important risk at present. Hands-down, the worst-case scenario for investors is a market that comes off of a syndrome of overvalued, overbought, overbullish conditions and then breaks trend-support in the context of an economic downturn. Market crashes are always driven by a spike in risk premiums from previously inadequate levels, and that sequence of events would be the perfect storm. (click here for full report) Continuing with our posts on the significant amount of tail-risk embedded in financial markets, Roach opines on global central bankers and their money-printing tendenciand consequences.

----- Stephen S. Roach July 2, 2013 Stephen S. Roach, Chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia and the firm's Chief Economist, is a senior fellow at Yale University’s Jackson Institute of Global Affairs and a senior lecturer at Yale’s School of Management. His most recent book is The Next Asia. NEW HAVEN – It was never going to be easy, but central banks in the world’s two largest economies – the United States and China – finally appear to be embarking on a path to policy normalization. Addicted to an open-ended strain of über monetary accommodation that was established in the depths of the Great Crisis of 2008-2009, financial markets are now gasping for breath. Ironically, because the traction of unconventional policies has always been limited, the fallout on real economies is likely to be muted. The Federal Reserve and the People’s Bank of China are on the same path, but for very different reasons. For Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke and his colleagues, there seems to be a growing sense that the economic emergency has passed, implying that extraordinary action – namely, a zero-interest-rate policy and a near-quadrupling of its balance sheet – is no longer appropriate. Conversely, the PBOC is engaged in a more pre-emptive strike – attempting to ensure stability by reducing the excess leverage that has long underpinned the real side of an increasingly credit-dependent Chinese economy. Both actions are correct and long overdue. While the Fed’s first round of quantitative easing helped to end the financial-market turmoil that occurred in the depths of the recent crisis, two subsequent rounds – including the current, open-ended QE3 – have done little to alleviate the lingering pressure on over-extended American consumers. Indeed, household-sector debt is still in excess of 110% of disposable personal income and the personal saving rate remains below 3%, averages that compare unfavorably with the 75% and 7.9% norms that prevailed, respectively, in the final three decades of the twentieth century. To continue reading, please click on the link below: http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/the-normalization-of-us-and-chinese-monetary-policy-by-stephen-s--roach |

A source of news, research and other information that we consider informative to investors within the context of tail hedging.

The RSS Feed allows you to automatically receive entries

Archives

June 2022

All content © 2011 Lionscrest Advisors Ltd. Images and content cannot be used or reproduced without express written permission. All rights reserved.

Please see important disclosures about this website by clicking here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed